How glass is made

Floating on a lake of tin

Last year, I took a glassblowing class at Brooklyn Glass.

I learned a couple of things:

I’ll never be a pro glassblower.

Glass SUCKS as a material.

It’s literally there to trick you. At room temp, it’s clear. At temps hot enough to give u 3rd degree burns, it’s clear. Then you have to heat it up even more, where it quickly goes to red (still can’t do anything with it) to orange. But then you have to see how orangey it is; if it’s orange it’s still too hard and won’t move at all, if it’s orange that’s perfect and just right, but you don’t want it to get ORANGE because then it’ll be too soft and droop straight off your pipe (hopefully not onto your shoe). The teacher could tell the difference, I think she was lying to us.

To start, you’ve got to stick a giant metal pipe into a lake of molten glass, and spin it fast enough that it picks up goopy glass like honey. Then you spend the next 30 seconds frantically spinning it and shaping it before it gets too droopy or too hard, only for you to have to chuck it into the furnace again every minute or so to soften again (but not too much bc ur shape will droop right off).

If you don’t cool it super slowly (annealing) it’ll crack or literally explode.

Also did I mention the glass 4 inches from your face is literally TWO THOUSAND degrees??

Anyway this whole blog post was just an excuse to show u this cool paperweight I made (look at it omg it’s so pretty). That’s another way of saying, the only shape I learned how to make was blob.

So what’s this blog actually about? Well, I’ve been really curious the last couple weeks about Industry (with a capital I), and started reading about industrial glassmaking - like windows and stuff. Here’s a info download for you:

glass history

For most of human history, making flat glass was brutally inefficient. Have you ever seen old-timey windows? They’re wiggly, not smooth, a little opaque.

Makes me think that staining glass was more of a practical choice than an aesthetic one (otherwise you’d just be living surrounded by funhouse mirrors).

In the 1840s, Henry Bessemer (yeah, the same guy who would make the Bessemer Process a couple years later) set up giant flat rollers to extrude out glass sheets. But this process still required extensive grinding and polishing, and let me tell you, you do NOT want to grind glass. Nevertheless, we spent the next HUNDRED years having british factory workers inhale glass dust.

By the 1950s, the glass industry was like a bird flying into a building in Manhattan. Unable to chart a safe course, and thus hitting a wall. (did u know 1000s of birds do this a year? Like 100 hit one world trade center alone. Turns out windows > birds in the food chain).

But between 1953 and 1957, the Pilkington Brothers developed FLOAT GLASS; what we still use today.

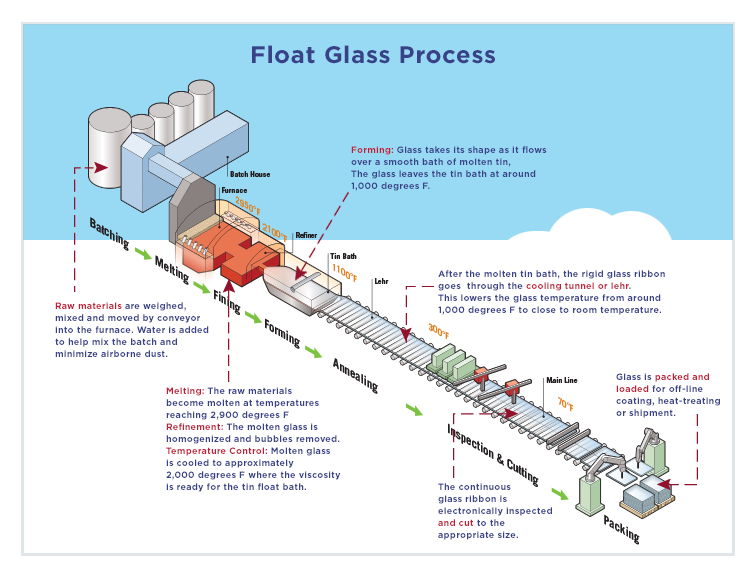

Here’s how it works.

Here’s how you got your floor-to-ceiling windows

The key insight is quite simple: what if glass could float on a perfectly smooth liquid surface, like oil on water?

Start off with a giant drum, filled with 72.6% sand, 13% soda, 8.4% limestone, 4.0% dolomite and 1.0% alumina. Chuck in a bunch of waste glass from further on in the process.

Then, heat up your mix in a kiln; it’ll turn to glass at 2700F or so. Cool it down until it’s got a honey-like viscosity, and it’s ready to float.

The next chamber is filled with a pool of molten tin. Tin is finicky; it oxidizes if exposed to air, and so the tin lake chamber is filled an atmosphere of nitrogen and a bit of hydrogen (which sucks up stray oxygen through H2 + O2 → H2O, i.e. burning it away). Otherwise, it’s perfect; it has a lower melting point than glass, and is denser. So the honey-like glass slowly pours onto the lake, and spreads out like a river: perfectly, atomically, flat.

Want thicker glass? Pour a bit faster. Thinner glass? Pour slower. There’s also thin rollers that can shove the glass river to flow a bit more slowly or quickly, thickening or thinning the final glass.

As the glass river flows, it cools; down to about 1000F, where it becomes solid. This tin lake runs continuously. On one end, molten glass gets poured in, and on the other, an endless sheet of perfectly flat glass rolls out.

The rest is more boring. A long, long, set of rollers carries the glass through an annealing chamber, where it slowly cools from super duper hot to room temp. It’s sliced into whatever shape the customer wants, and the extra bits are crushed and sent back to the beginning. Stack and ship.

These furnaces run 24/7 for up to 15 years. You can't just turn them off for the weekend; the thermal mass is so enormous that cooling down and restarting would take months and cost millions. That means that any interruption to power or natural gas supply is very, very, expensive. Production rates reach 6000 tons a week, enough glass to cover 30-50 football fields daily from a single line. And each pane is microscopically flat: over 0.5mm, they only go up or down by around 2-3 nanometers.

And, at the end, we get fancy floor-to-ceiling windows.

excellent article. Thanks Daniel.