Indestructible Glass Blobs

Prince Rupert's Drops and physics

Glass vs bullet. Who wins?

Glass does (well, until the end…).

That’s a clip from these super awesome videos about Prince Rupert’s Drops.

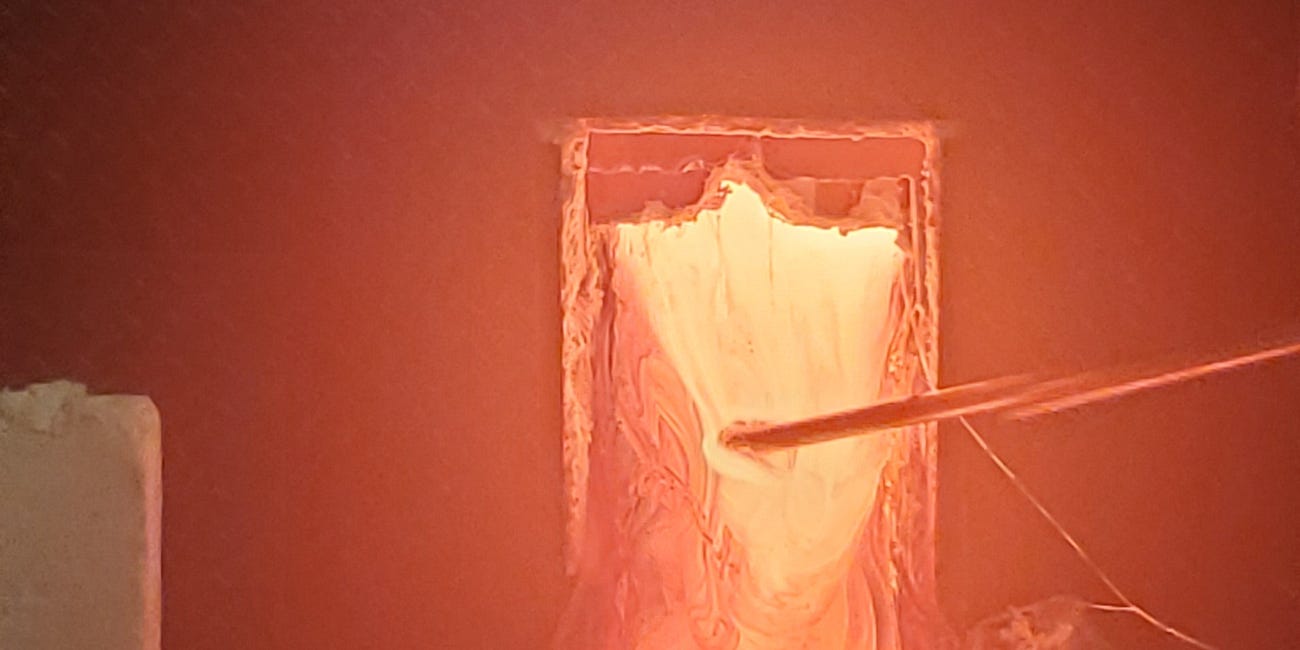

Take molten glass and drop it into cold water (my glassblowing studio would be furious). You get a teardrop-shaped glass blob with a superpower: its bulbous head can withstand hammer blows that would shatter a normal piece of glass. You can shoot it, crush it in a vice, or smack it against concrete. The thing won’t break.

But if you flick the thin tail, the entire object explodes into powder in a fraction of a millisecond. Not shatters. Explodes.

These are called Prince Rupert’s Drops, named after the 17th century Prince who made them famous in England. Apparently, he kept showing everyone at his house parties, until everyone knew about it and told him his trick was super lame. It’s like what happens if your cousin found a glass kiln instead of magic tricks…

But anyway, I was nerdsniped, and also mildly embarrassed that I hadn’t heard of these guys before (I’d be tittered out of 17th century noble parties).

How it works

The recipe is simple but the result is anything but. You heat glass until it’s molten, around 1000C, and drip it into a bucket of cold water. The outside of the droplet hits the water and solidifies almost instantly. But the inside is still molten, still hot, still trying to cool down and contract.

As the interior cools over the next few seconds, it shrinks. But it can’t shrink freely because it’s trapped inside a solid shell that’s already set. The result is a frozen war of opposing forces. The outer layer gets compressed inward; squeezed by the shrinking interior. The inner core gets stretched outward; pulled by the rigid exterior. Neither can move. They’re locked in place.

Think of it like this: imagine a coiled spring you’ve compressed and then somehow stuck it in an indestructible box. It’s holding enormous potential energy, but it can’t release it. That’s what’s happening in the head of a Prince Rupert’s Drop. The outer shell is under tremendous compressive stress—around 700 megapascals, making it incredibly resistant to fracture. When you push down on the box, the spring is already primed to counteract you; the box will simply squeeze the spring “less” than when you weren’t helping, while you huff and puff and watch the box stay exactly the same shape.

And these drops end up super strong. This dude on reddit fucked up his hydraulic press trying to crack it.

This is the exact principle behind tempered glass; the stuff in your car windows and phone screen. When manufacturers make tempered glass, they heat it up and then blast it with cold air. Same deal: outer layer cools and hardens first, inner layer shrinks and puts everything under stress. Your car window can take a beating because its surface is compressed. Gorilla Glass on your phone? Same concept, but instead of thermal stress, they use a chemical process to stuff larger ions into the surface, creating compression. But the principle is identical: frozen stress makes glass tough.

The Achilles Tail

So if the head is indestructible, why does the tail doom the whole thing?

The tail forms as the molten glass stretches during the fall into water. It cools chaotically, sometimes twisting, always thin, and never with the uniform stress distribution of the bulbous head. It’s riddled with flaws and stress concentrations.

When you snap the tail, you create a crack. And cracks in brittle materials like glass have a particular job: they want to relieve stress, and they accelerate exponentially once they get going; as a bigger and bigger tear tries to push apart a smaller and smaller length of glass.

A crack is essentially the material’s way of releasing stored elastic energy. In the tail, there’s not much resistance. The crack zips through and hits the inner core of the head, meeting that stretched interior that’s been held in check by the compressed exterior.

That’s when things go catastrophic. The crack suddenly has access to an enormous reservoir of stored energy. In materials science, there’s a formal framework for this called the Griffith criterion, which essentially says a crack will propagate when the energy released by crack growth exceeds the energy required to create new surfaces. In a Prince Rupert’s Drop, that calculation isn’t even close. The crack accelerates to around 1,500 meters per second, faster than the speed of sound in glass. If you were inside the glass, you’d feel a sonic boom (and it would hurt a lot). The whole object disintegrates in about a millisecond.

This is why brittle materials are so unforgiving. A metal might dent or deform when stressed, dissipating energy through plastic deformation. Glass can’t do that. It stores the energy elastically until something gives, and then it gives catastrophically. This is why you don’t make airplanes out of ceramic, even though ceramics can be incredibly strong. One tiny flaw, one propagating crack, and the whole structure is compromised.

It’s also why quality control matters so much in brittle materials. A microscopic surface scratch on a glass component can be a death sentence. No wonder glass windows are made floating on a lake of tin!

Pre-Stressing generally

The engineering principle here is actually quite cool. Putting materials under deliberate, permanent stress can make them stronger. It’s counterintuitive: shouldn’t stress weaken things? But it works because you’re strategically loading the material in ways that offset the loads it’ll face in service.

Prestressed concrete is the clearest example. Concrete is great at being compressed, i.e. you can stack enormous weights on it, but terrible in tension. Even modest tensile loads will crack it. So engineers figured out a clever trick: embed steel cables in the concrete, pull them tight, and lock them in place. Now the cables are under tension, and they’re pulling the concrete inward, compressing it. When you load the structure, the concrete first has to overcome that compressive stress before it experiences any tension.

So we’re back where we started: a glass teardrop that won’t break until it explodes. The frozen stress that makes the head indestructible is the same stored energy that makes the whole object disintegrate when the tail breaks. You can’t have one without the other. Sometimes being under pressure is exactly what makes something strong. The trick is making sure the pressure is in the right place, pointing in the right direction, and that you never, ever break the tail.